In meditation, when things don’t go our way, we tend to resist. Feeling restless? Then fidget incessantly as a way of not feeling the restlessness or what may be behind it. Have a hard time focusing on your breath? Then berate yourself as a bad meditator and despair at ever getting “good” at the practice.

In meditation, when things don’t go our way, we tend to resist. Feeling restless? Then fidget incessantly as a way of not feeling the restlessness or what may be behind it. Have a hard time focusing on your breath? Then berate yourself as a bad meditator and despair at ever getting “good” at the practice.

It’s like this in daily life as well. If someone has betrayed us, we might spend a lot of time ruminating about how the betrayal shouldn’t have happened, about how the person had no right to do it, and perhaps float creative ideas for getting revenge. Your candidate didn’t win an election? Then blame those who didn’t vote, or shame certain groups of people as being somehow less worthy of your respect. Or begin fantasizing about moving to Canada.

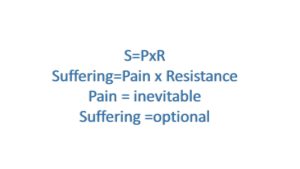

The problem with resistance is that it tends to make things worse. There’s an old Buddhist teaching about the two arrows. The first arrow that hits you is the inevitable pain of life. The second arrow that hits you is your resistance to your pain. You may not be able to control the inevitable pains and sorrows of life – in fact, count on that. But you can control how you respond to your pain. In a more modern context (via teacher Shinzen Young) we can describe it as an equation of suffering, as:

When our minds are untrained, or when our training is forgotten, our default way of handling a stressful event is to lash out and resist based on our unconscious habit patterns, biases, and personal conditioning. We are on auto pilot and have no chance to accurately appraise the situation. Instead we try to fix, attack, control, rationalize, blame others, or avoid the truth of what’s been happening in the deluded hope that such tactics will somehow make us feel better. When we swat a fly that’s been crawling on us, we may be removing the discomfort of that experience – but we’ll end up knowing very little about flies. This is certainly true for those humans who annoy us as well. We can swat them away but what will we learn about them or what motivates them?

In contrast, when our minds are trained our default way of handling a stressful event is first to allow things to be as they are. That doesn’t mean liking or agreeing with the suffering we’re experiencing. It means giving space to it in a way that helps us metabolize it physically, mentally, and emotionally. Research has shown that when people can be with things as they are, the parasympathetic nervous system is activated. This is often referred to as the “rest and digest” function of the nervous system, or the relaxation response. When we take time to digest the pain we are experiencing, the body can relax and the mind can become still and clear. Not only can suffering be seen clearly, but the natural wisdom of the mind can begin to reveal the appropriate response.

Non-resistance doesn’t mean that we ignore injustice. In fact, non-resistance can help cultivate a more sustainable ability to resist injustice. Because when we can first be with things as they are, letting the shock and anger metabolize first, we then can practice political resistance in a responsive way – not in a reactive way. In other words, you may be fighting against oppression, racism, misogyny, and other forms of harm, but you are in control of your mental states. You are not acting because you are overwhelmed, addled with rage and fear, you are responding with awareness to suffering. Your heart and mind are steady, clear. You will not get burned out in the face of a long struggle for justice, because you are taking care of yourself. And this steadiness of mind in the face of oppression can be supported by not resisting the truth of a bad situation. The bad situation is already here; if we don’t give in to our habitual fight or flight reactions to it, let’s see how the wise and compassionate heart responds.

When you’re working really hard and it’s time to take a break, what do you do? What does it mean to take a break? Is a break walking away from your desk while checking out your phone for messages, visiting Facebook for updates from friends, or browsing your favorite news blog? Is taking a break eating at your desk while web browsing? Or is it visiting a colleague to have a business conversation? Many people believe they have to be productive all the time, so even when they take a “break” they have to do something potentially useful. (A student of mine once confessed that when she brushed her teeth at night, she was texting friends with her free hand. She explained that brushing her teeth wasn’t accomplishing enough!) The problem with these kinds of breaks is that they keep the mind focused on conceptual experiences. But a true break means we are giving the brain a break from concepts. Brain scans have shown that when people are focused on concepts – doing work, for example – many regions of the bran light up. The brain is expending a lot of energy when we are doing things that take conceptual focus. When we expend this kind of energy without pause, hour after hour, it can be quite exhausting. When we are exhausted, our performance suffers, our inner sense of well-being declines, and our health can suffer as well. Burnout and lack of engagement often follow.

When you’re working really hard and it’s time to take a break, what do you do? What does it mean to take a break? Is a break walking away from your desk while checking out your phone for messages, visiting Facebook for updates from friends, or browsing your favorite news blog? Is taking a break eating at your desk while web browsing? Or is it visiting a colleague to have a business conversation? Many people believe they have to be productive all the time, so even when they take a “break” they have to do something potentially useful. (A student of mine once confessed that when she brushed her teeth at night, she was texting friends with her free hand. She explained that brushing her teeth wasn’t accomplishing enough!) The problem with these kinds of breaks is that they keep the mind focused on conceptual experiences. But a true break means we are giving the brain a break from concepts. Brain scans have shown that when people are focused on concepts – doing work, for example – many regions of the bran light up. The brain is expending a lot of energy when we are doing things that take conceptual focus. When we expend this kind of energy without pause, hour after hour, it can be quite exhausting. When we are exhausted, our performance suffers, our inner sense of well-being declines, and our health can suffer as well. Burnout and lack of engagement often follow.

I am extensively quoted in

I am extensively quoted in

I recently returned from a 9-day intensive meditation retreat focused on the practices of concentration and mindfulness. The first four days of the retreat presented me with the usual struggle – re-learning how to slow down, quitting caffeine, abandoning cell phones, blogs and the internet, and mostly, just watching the habit patterns of my mind replay themselves ad nauseum. By day five I was really settling in nicely, my mind was calmer, clearer, and more focused, and I was able to steady my attention on the breath – and even more interestingly to me – the stillness of knowing the breath. I was really beginning to hit my stride and was looking forward to deepening my concentration in the following final days of the retreat. But on Sunday night, instead of listening to that night’s talk on practice with my fellow practitioners, I found myself in the emergency room of the nearest hospital with an IV drip of saline in my arm.

I recently returned from a 9-day intensive meditation retreat focused on the practices of concentration and mindfulness. The first four days of the retreat presented me with the usual struggle – re-learning how to slow down, quitting caffeine, abandoning cell phones, blogs and the internet, and mostly, just watching the habit patterns of my mind replay themselves ad nauseum. By day five I was really settling in nicely, my mind was calmer, clearer, and more focused, and I was able to steady my attention on the breath – and even more interestingly to me – the stillness of knowing the breath. I was really beginning to hit my stride and was looking forward to deepening my concentration in the following final days of the retreat. But on Sunday night, instead of listening to that night’s talk on practice with my fellow practitioners, I found myself in the emergency room of the nearest hospital with an IV drip of saline in my arm.

The human mind is beautiful, but also dangerous. Our thoughts and emotions can be powerful drivers of our behavior. Since many of our mind-states are negative, our actions are often at the mercy of our thoughts. Gloomy and pessimistic thinking, long established from habit, creates rigid and stereotyped narratives psychologists have labeled cognitive distortions. You probably know some of these stories from your own experience. They often begin with, “I’ll never be good at this because,” or “I’ll never be loved because,” or “My pain will always be like this because,” etc. These stories become so familiar to us that they define who we think we are or can become. And the actions we take in the world reflect the limitations of this thinking.

The human mind is beautiful, but also dangerous. Our thoughts and emotions can be powerful drivers of our behavior. Since many of our mind-states are negative, our actions are often at the mercy of our thoughts. Gloomy and pessimistic thinking, long established from habit, creates rigid and stereotyped narratives psychologists have labeled cognitive distortions. You probably know some of these stories from your own experience. They often begin with, “I’ll never be good at this because,” or “I’ll never be loved because,” or “My pain will always be like this because,” etc. These stories become so familiar to us that they define who we think we are or can become. And the actions we take in the world reflect the limitations of this thinking.